.45-70

| .45-70 Government | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| .45-70 Government | |||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Rifle | ||||||||||||||||||

| Country of Origin | USA | ||||||||||||||||||

| Specifications | |||||||||||||||||||

| Case Type | Rimmed, straight | ||||||||||||||||||

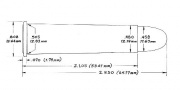

| Bullet Ø | .458 in (11.6 mm) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Neck Ø | .480 in (12.2 mm) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Base Ø | .505 in (12.8 mm) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rim Ø | .608 in (15.4 mm) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rim Thickness | .070 in (1.8 mm) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Case Length | 2.105 in (53.5 mm) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Full Length | 2.550 in (64.8 mm) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rifling twist | 1-20" | ||||||||||||||||||

| Primer | Large rifle | ||||||||||||||||||

| Production & Service | |||||||||||||||||||

| Designer | US Govt | ||||||||||||||||||

| Design Date | 1873 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Used By | United States | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ballistic Performance Sampling | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Contents |

[edit] Nomenclature

The new cartridge was completely identified as the .45-70-405, but was also commonly called the ".45 Government" cartridge in commercial catalogs. The nomenclature of the time was based on several properties of the cartridge:

- .45 : nominal caliber, in decimal inches i.e. 0.45 inches (11.4 mm)

- 70 : wt. of blackpowder charge, in grains i.e. 7000 grains 1 pound

- 405 : weight of lead bullet, in grains i.e. 405 grains (26.2 g)

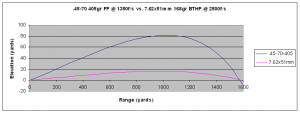

The minimum acceptable accuracy of the .45-70 from the 1873 Springfield was approximately 4 inches (100 mm) at 100 yards (91 m), however, the heavy, slow-moving bullet had a "rainbow" trajectory, the bullet drop measured in multiple yards (meters) at ranges greater than a few hundred yards (meters). A skilled shooter, firing at known range, could consistently hit targets that were 6 X 6 feet (1.8 m) at 600 yards (550 m) — the Army standard target, and a skill mainly of value in mass or volley fire, since accurate aimed fire on a man-sized target was effective only to about 300 yards (270 m).

After the Sandy Hook tests of 1879, a new variation of the .45-70 cartridge was produced, the .45-70-500, which fired a heavier 500 grain (32.5 g) bullet. The heavier 500-grain (32 g) bullet produced significantly superior ballistics, and could reach ranges of 3,500 yards (3200 m), which were beyond the maximum range of the .45-70-405. While the effective range of the .45-70 on individual targets was limited to about 1,000 yards (915 m) with either load, the heavier bullet would produce lethal injuries at 3,500 yards (3,200 m). At those ranges, the bullets struck point-first at roughly a 30 degree angle, penetrating 3 one inch (2.5 cm) thick oak boards, and then traveling to a depth of 8 inches (20 cm) into the sand of the Sandy Hook beach*. It was hoped the longer range of the .45-70-500 would allow effective volleyed fire at ranges beyond those normally expected of infantry fire[4].

[edit] Bullet diameter

Note that while the nominal bore diameter was .45 inches (11 mm), the groove diameter was actually closer to .458 inches (11.6 mm). As was standard practice with many early U.S. commercially produced cartridges, specially-constructed bullets were often "paper patched", or wrapped in a couple of layers of thin paper. This patch served to seal the bore and keep the soft lead bullet from coming in contact with the bore, preventing leading (see internal ballistics). Like the cloth or paper patch used in muzzleloading firearms, the paper patch fell off soon after the bullet left the bore. Paper patched bullets were made of soft lead .450 inches (11.4 mm) in diameter. When wrapped in two layers of thin cotton paper, this produced a final size of .458 inches (11.6 mm) to match the bore. Paper patched bullets are still available, and some black powder shooters still "roll their own" paper patched bullets for hunting and competitive shooting.[5] [6] Arsenal loadings for the .45-70-405 and .45-70-500 government cartridges generally used groove diameter grease groove bullets of .458 inches (11.6 mm) diameter.[7][edit] History

The predecessor to the .45-70 was the short lived .50-70-425 cartridge, adopted in 1866 and used in a variety of rifles, many of them percussion rifled muskets converted to trapdoor action breechloaders. The conversion consisted of milling out the rear of the barrel for the tilting breechblock, and placing a .50 caliber "liner" barrel inside the .58 caliber barrel. The .50-70 was popular among hunters, as the bigger .50 caliber bullet hit harder (see terminal ballistics) but the military decided even as early as 1866 that a .45 caliber bullet would provide increased range, penetration and accuracy. The .50-70 was nevertheless adopted as a temporary solution until a significantly improved rifle and cartridge could be developed.

The result of the quest for a more accurate, flatter shooting .45 caliber cartridge and firearm was the Springfield Trapdoor rifle. Like the .50-70 before, it, the .45-70 used a brass center-fire case design. A reduced power loading was also adopted for use in the Trapdoor carbine. This had a 55 grain (3.6 g) powder charge.

Also issued was the .45-70 "Forager" round, which contained a thin wooden bullet filled with birdshot, intended for use hunting small game to supplement the soldiers' rations[8]. This round in effect made the .45-70 rifle into a 49 gauge shotgun.

The 45 caliber rifle underwent a number of modifications over the years, the principal one being a strengthened breech starting in 1884. A new, 500 grain (32 g) bullet was adopted in that year for use in the stronger arm. The 45 caliber rifle was the principal arm of the US Army until 1893, long after European adoption of efficient repeaters using smokeless powder ammunition had made the American weapon obsolete as a military rifle. It was last used in quantity during the Spanish-American War, and was not completely purged from the inventory until well into the 20th century. Many surplus rifles were given to reservation Indians as subsistence hunting rifles and now carry Indian markings.

The .45-70 cartridge is still used by the U.S. military today, in the form of the CARTRIDGE, CALIBER .45, LINE THROWING, M32, a blank cartridge which is used in a number of models of line throwing guns used by the Navy and Coast Guard. Early models of these line throwing guns were made from modified Trapdoor and Sharps rifles, while later models are built on break-open single-shot rifle actions[9].

[edit] Sporting use

As is usual with military ammunitions, the .45-70 was an immediate hit among sportsmen as well, and the .45-70 has survived for one and a third centuries. Today, the traditional 405 grain (26.2 g) load is considered adequate for any North American big game within its range limitations, including the great bears, and it does not destroy edible meat on smaller animals such as deer due to the bullet's low velocity. It is very good for big game hunting in brush or heavy timber where the range is usually short.

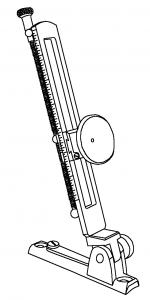

The main limitation of the .45-70 is the relatively low velocity which puts a practical limit on shots at game beyond 120 meters or so, despite its ability to kill at many times that distance. The trajectory of the bullets is very steep, which makes for a very short point blank range. This was not a significant problem at the time of introduction, as the .45-70 was a fairly flat-shooting cartridge for its time. Shooters of these early cartridges had to be keen judges of distance, wind and trajectory to make long shots; the Sharps Rifle in larger calibers such as .50-110 was used at ranges of 1,000 yards (910 m). Most modern shooters use much higher velocity cartridges, relying on the long point blank range, and rarely using telescopic sight's elevation adjustments, calibrated iron sights, or hold-over. Sights found on early cartridge hunting rifles were quite sophisticated, with a long sighting radius, wide range of elevation, and vernier adjustments to allow precise calibration of the sights for a given range[10]. Even the military "creedmoor" type rifle sights were calibrated and designed to handle extended ranges, flipping up to provide several degrees of elevation adjustment if needed[11]. The .45-70 is a popular choice for black powder cartridge shooting events, and replicas of most of the early rifles, including Trapdoor, Sharps, and Remington single shot rifles, are readily available.

The .45-70 retains great popularity among American hunters for the niche it is suited for, and is still offered by several commercial ammunition manufacturers. Although loaded with modern smokeless powders, in most cases pressures are kept low for safety in antique rifles and their replicas. Various modern sporting rifles are chambered for the .45-70, and some of these will benefit from judicious handloading of home-made ammunition with markedly higher pressure and ballistic performance. Others, which reproduce the original designs will take the original load, but are not strong enough for anything with higher pressure. In a rifle such as the Siamese Mauser or a Ruger single shot, it can be handloaded to deliver good performance even on big African game. Instructions in book form and specialized reloading tools for duplicating the original arsenal load with a full 70 gr. charge of black powder are available from Wolf's Western Traders.

In addition to its traditional use in rifles, Thompson Center Arms has offered a .45-70 barrel in both pistol and rifle lengths for their Contender single shot pistol, arguably the most potent caliber offered in the Contender frame. Even the shortest barrel, 14 inches, is easily capable of producing well over 2,000 ft·lbf (2,700 J) of energy, double the power of most .44 Magnum loadings, and a Taylor KO Factor as high as 40 with some loads. Recent .45-70 barrels are available with an efficient muzzle brake that significantly reduces the muzzle rise and also helps attenuate the tremendous recoil. The Magnum Research BFR is a heavier gun at approximately 4.5 pounds, helping it have much more manageable recoil.[12]

Only with the recent introduction of ultra-magnum revolver cartridges such as the .500 S&W Magnum have production handguns begun to eclipse the .45-70 Contender in the rarefied field of big-game capable handguns.

[edit] See also

- List of rifle cartridges

- 11 mm caliber other cartridges of similar caliber.

- .458 SOCOM

- .450 Marlin

- .444 Marlin

[edit] References

- ↑ .45-70 data for Trapdoor from Accurate Powder

- ↑ .45-70 standard data from Accurate Powder

- ↑ .45-70 data for Strong actions from Accurate Powder

- ↑ .45-70 at Two Miles: The Sandy Hook Tests of 1879

- ↑ ^ Venturino, Mike (November 1, 2006). "Loading paper patch bullets: exploring the past through its tools.". Guns Magazine.

- ↑ Making, Loading, and Shooting aper Patched Bullets

- ↑ Wayne van Zwoll, .45-70 GOVERNMENT Petersen's Hunting

- ↑ .45-70 Forager round, picture and information

- ↑ CG-85 Coast Guard approved .45-70 line launching kit

- ↑ Montana Vintage Arms reproduction tang sight of the type commonly used on hunting rifles in the late 1800s

- ↑ Trapdoor carbine rear sight, ladder type, with calibrated ranges out to 1,200 yards (1,100 m)

- ↑ Hogdon publishes load data for the .45-70 in pistols; one listed load shows a 300-grain (19 g) bullet at 2,076 ft/s (633 m/s), generating over 2,800 ft·lbf (3,800 J). and a Taylor KO factor of just over 40

- .45-70 Government by Chuck Hawks

- The Good Old .45-70 Government by Chuck Hawks (subscription required)

[edit] External links

- Breech-Loaders In The United States, The Engineer, 11 January 1867, on the adoption of a military breech loading rifle and cartridge

- Shoot! Magazine article on the .50-70 cartridge